Showed on the screen the syllabus (link to it) https://c7riochico.net/ant/

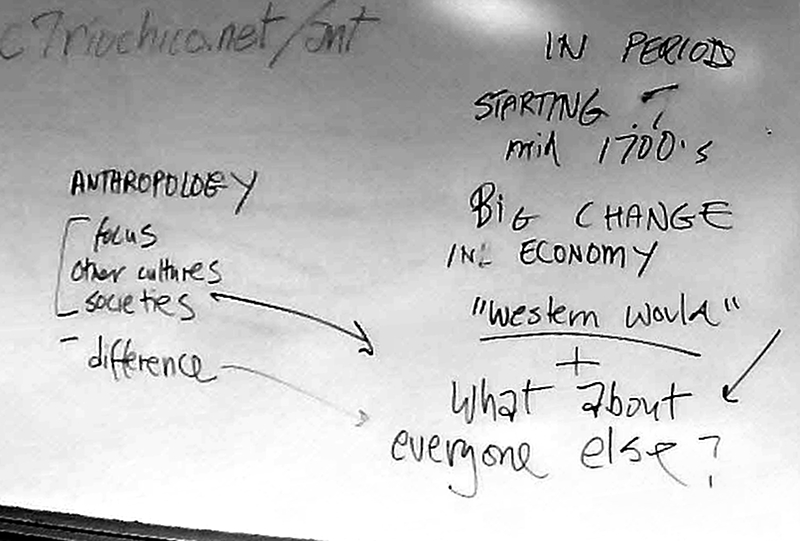

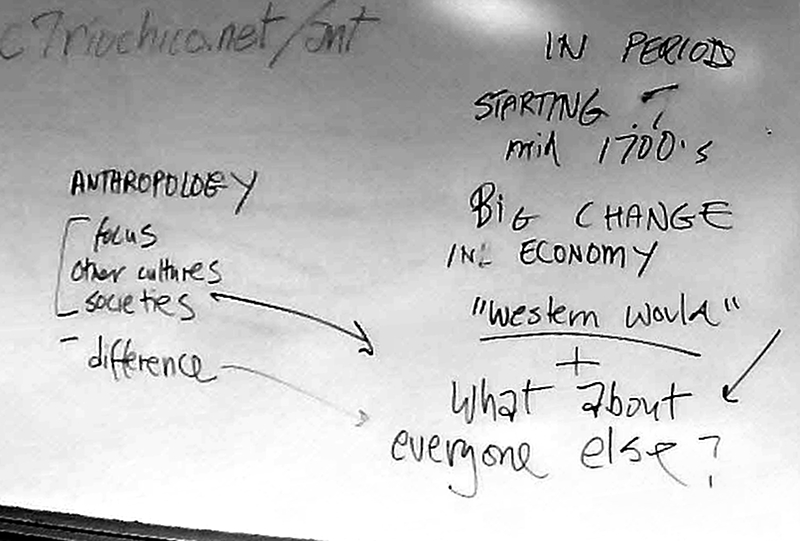

what was on the board by the end more or less:

|

|

Hello this is Introduction to Anthropology and I am Prof. Hugh Gladwin. [writing ANT2000 on board]

Today what I want to do is describe the class for you, what's expected and give you the most basic concept of the field of anthropology that the class is about. This is a class that should be interesting, a good introduction to my field. At the same time it's kind of not for everyone in a sense that I'll try to explain more. There is a lot in anthropology that is very personal, contentious, and reflecting an individual viewpoint, and to do well in the class or at least get the idea, you don't necessarily have to change your personality, but you have to be flexible in a way that sometimes people find difficult. In a lot of classes there is definite material that's cut and dry, you use it, you learn it, you take tests, and if you learn it all and you can write about it and so on you get a good grade. The material is there, it's kind of agreed on like that's the way it is. Unfortunately, in anthropology, the basic subject matter of the field is trying to understand different cultures and different ways people are. And that goes to the field itself--there are different views within anthropology about the way people are. So it's more of a method for finding out about different cultures and different people than a fixed body of knowledge--I'll go into that more in a minute. But that's something you should think about today.

To do well in this class I hope you'll have an open mind and be flexible about reading about different theories, some of which you will disagree with and learning about different people in different cultures, some of which you'll say, my God, why are they like that, I'm not like that. We are not saying that you have to believe everything you hear in here or change yourself, or attack your own personal moral values. But there's a problem for you in this class, if your mode is always, I know what's right. I know what I am. Anything that is really different for me is wrong or weird or whatever like that--those are natural feelings that we all have. But again, in this class, it's not a class where you're expected to be converted or agree with everything, but you have to be open minded, because the sort of methodology of anthropology which we call ethnography really is about trying to put yourself in the place of other people in other cultures and see how they work. What kind of sense they make. What their history is. What their values are. Again, you don't have to become like [them] but you have to put aside for a moment your initial reactions and really be open about [them].

So in the course of the class (and I'm going to talk about the specifics in a minute) but we are using a textbook which presents a lot of case studies--very short case studies--of different cultures in society that anthropologists have done that give you an idea of the kind of work that's been done. And also along with that, in the book and in my lectures and so on, there is a body of knowledge that anthropologists have sort of come to. I wouldn't say "agree on" because almost everything is argued about as things are discussed. So I'll get more into how that works in the class but again this is a class not for you to debate different philosophies and take your beliefs and challenge others. ---you can get to that . . . we will get to that eventually perhaps as part of the class, but to start off with that you're open minded and you try to use these methods, be an anthropologist, to see how other cultures work.

Okay so let me give out the syllabus . . . Now the main parts of the syllabus are to be discussed here today, so the most important parts we have to talk about. So like I say, this is not going to tell you very much right now about the class other than when it is, office hours scheduled, rough schedule of readings that will probably change. If you go to Blackboard right now there's a link to the syllabus, that's all that's there today and the link will take you to be here [to syllabus projected on screen], so . . .

Let me just quickly go over some technicalities: I'm based at the BBC campus. My office is there. So as far as office hours go, the basic thing is you if you want to see me there is a time at BBC but most of you probably don't go up there. The main thing is to email me. I'm always watching emails so we can agree to meet before or after this class or whatever. This is my email address gladwin@fiu.edu. That's the main way to communicate with me. I am a sort of avid emailer so I do try to keep track if you email me, and if you don't hear back within a day, follow-up, let me know what happened. Now to give a better chance of making email addresses work, there are a few rules. First off, always use my FIU email address. Do not use Blackboard. I just always have constant problems on Blackboard mail and it's not consistent for me, you'll see that I not a big fan of Blackboard, even though obviously it will be a main thing for us to be using. But the problem is if you email me on Blackboard email then your likely did not hear back for a week or something. So please use FIU email. The other thing is when you send me an email always put ANT2000 in the subject of the email anywhere in the subject line like this ANT in caps and no space between it and the 2000. That flags the email so I see it much more quickly. I will get it, probably, if you don't do that, but it really helps to do that. In just a minute I'm going to give you the option of using another email [address].

I just put a little note here [in the syllabus] that this is a UCC Social Science Class, but most particularly, it's a Global Learning designated class which means that we have some required material and exercise which actually fits totally well in the framework of anthropology to do.

I also would like you to fill out a short student information form and to do that, you can either go to Blackboard or this alternative site where I'll be putting a lot of stuff up on this other server. That should do it if you go there. That should give you a copy of the syllabus--that's where [the link on] Blackboard takes you to. You can also write this down from the syllabus you have and type it in. There is a very short Qualtrics form here with just a few questions to facilitate communications, so is just name, student ID. Your name is you normally like to be called, your FIU email address, and then here you can put down another email address so, if you have one other email address that you use a lot, put that down. Make sure you spell it right and then all emails I send to you will go both to your [FIU] email address and that email address. That still means you should check your FIU email at least once a day because some things come out from Blackboard and then they only go to your FIU email address, and then finally, this is completely optional, but if you put down a cell phone number where I could reach you if class is suddenly canceled or some major thing happens. Again, this is optional, but it gives gives us a chance to reach you if there's an emergency. Finally any questions or comments you have about the class. If you fill it out, you can go back and fill it out again but if you fill it out the second time I'll ask you to put all the information back in the second time so will all be there in the last recorded one. But if you want to add a comment later. So that's that there.

I also put this here about the eclipse just so we can . . . probably [connection] overwhelmed I guess . . . So this is a little video of what starting at 145 clock so we'll be at this when we're done will be definitely out by 240 so you can if you have time you go see what's going on out there. I would remind you for safety that the problem with being in this location there for the eclipse there are two problems. Some you know one is even though the sun is a lot covered up. There's still plenty of sunlight coming through so it doesn't really get dark and impressive but the other thing is when it at maximum eclipse-- normally you don't look at the sun because it hurts your eyes to stare at the sun, but the problem with the eclipse the sun is mostly covered, so it seems like it's not so bright, seems like you can look at it but in fact you can damage your retina by looking at it because that piece of the sun that you see is going to hit your retina with incredible brightness and people after eclipse like this people in areas like this where that doesn't cover up do often damage their eyes by staring at it. So just a health warning you can, by the way, supposedly look at it on the ground by taking a card or something and making a little hole in it and it projects down called a camera obscura and you can actually do that with your fingers. But if you have time if you don't have a class after this and will try to get out little bit early. I'm sure they have all kinds of stuff next-door out there so you can do it.

So anyway little bit of non-anthropology, but it is relative I just saw a tweet or something this morning somebody sent me that said things have gotten so bad I'm going to ask God to send a sign, and blot out the sun today to show us he's unhappy with what's going on. But that's one thing we'll get into in this class is different beliefs about religion and so on. And you know eclipses actually have had tremendous religious meaning and things in different cultures. One thing we will talk about is some societies that have believed like the ancient Maya in Mesoamerica that humans know the gods are not necessarily good [all the time]. The gods do all kinds of unpleasant things with people, and you really have to be able to know what they're up to. One way you can do that is by reading the stars in predicting things and for the Maya things like lunar eclipses were indications of the unhappiness of the gods, and one of the problems with the gods and the Mayan culture was that the gods had these signs like eclipses and the appearance of Venus that indicated that they were unhappy and people needed to really try hard and do good things to make the gods happy to do whatever type of things would make the gods happy, but it was sort of the eclipse would be the thing that triggered what the gods were going to do so. The problem for people is if you didn't know when that was going to happen, you could not be specially conforming to what the gods wanted ahead of time, so the Maya invested in enormous efforts in astronomy and we see the records of that in the inscriptions and things they have left. But I believe they were able to predict lunar eclipses with great accuracy and a lot of other things too. So for them, there was a religious purpose in it.

That's typical of some of the stuff that we will be doing here [in this class]. Is this eclipse a sign that God is not pleased with what's going on by blotting out the sun? Well, probably most of our own personal theories is that that's probably not the case. But the thing is you need to think about the fact that in some places and for some people it would be a sign. And what's complicated, as will see, is that you know there's a lot of debate over whether anthropology ( . . . I'm kind of being indirect, haven't really defined it yet, but anthropology is the study of mankind . . .), but a lot of debate over whether anthropology really is a science or part of the humanities. My position on this is one of many where I disagree with some of my fellow anthropologists because I do think it's a science, but my view of the science is that what is in any of the sciences, what scientists say,is not the truth. It's actually a fiction, it is an account of how things are with nature -- nature including the natural world and the human world which we have ways of interacting with other people that anthropology we call ethnography -- and if we do it right we hope that that can take us closer to a better understanding of what's going on or what is what is there in reality but it's never the total truth. So as anthropologists . . . say we are talking to somebody who feels like the eclipse is God blocking out the sun to express his or her displeasure or Mayans talking about a lunar eclipse being a sign that people have to be specially vigilant to keep the gods happy . . . as an anthropologist that is a theory about nature, about things, that just as possibly valid as this so-called scientific theory because the scientific theory that Western astronomy would produce has all kinds of questions in it. I mean the [ancient] Maya astronomer would say, well you know, yeah, at 2 o'clock like that thing you just showed, were going to have in a eclipse. But yeah, I mean, just look at all these inscriptions, all the [lunar] eclipses we predicted [note Prof G: I don't believe they were ever able to predict predict solar eclipses because they're so rare, not enough data]. But you know if we could predict it too, so what's the difference? Well, the difference is your theory of the mechanism and our theory that the gods are doing it. So we can say, well, the scientific theory you use of astronomy is more true. . . . well it's really more true, but it isn't really. All we would say is there's more evidence for it, it doesn't mean it's true. And the thing is, if we [non-Maya] just say flat out, well you Mayans are wrong, you know there's no mechanism by which the gods would like be able to arrange that. The Mayan [astronomer] would probably say well I can accept that you say that, but your theory says absolutely nothing about the way people are supposed to act, about values, about our religion, or anything like that. It would be be sort of like saying for a religious holiday that is important in a religion the scientific explanation is that it comes three weeks before the summer solstice or something like that. So does that mean that the religious holiday is explained by astronomy? Well, the date of it is, but you are not understanding that religion at all if you do [only] that.

OK now you have an idea of one of the problems of this class which is the way I ramble on which gets to how the class is organized. So let me just quickly go over some of the things in the syllabus and to be discussed in the first class--we'll do that. So this is the textbook. This book is been around. This is the 15th edition which you do need to get because it changes all the time. Every time it comes out they put in case studies and bring some back so you need to have the current 15th edition but I think you can rent it or buy used or whatever but we will be using this book a lot. You absolutely have to get it in one form or another, so please go ahead and do it . . . . [question when is the first time we will be using the book?] The first use of the book is pretty much now because the way we are going to go through this class is we will cover the book in sections so the first section, culture, and ethnography is chapters 1 to 4 so I'm expecting you to read that by the next class as you can see in the syllabus so and normally we will be reading like five [chapters], for the [class] day there will be material on it, there will be quizzes and stuff like that, so you really need to get the book. You know it's, again it's because it's descriptions of other cultures as I will get to in a minute -- we are going to be talking about them in [each] class. So you really have to read -- I will expect you to have read the chapters for each week before the class. So you need to get the book and before we meet on Monday, you need to read those four chapters. So that's basically that.

About the organization of this class. This class is what we call in GSS (I don't know if other departments have it) a hybrid class but a kind of special hybrid slightly illegal hybrid I'm not exactly sure. Basically the way it works is we meet once a week. If you look at the amount of hours roughly I consider that you're doing two thirds of the class in here in class, but you're expected to spend extra time working on stuff online or working outside of the class doing stuff. So what this actually means is that I feel like we can focus more on interactive stuff in discussions and lectures in the class and then there will be other material for you to get online. Although the main material is the book so it's kinda like strange in a way because I feel like a lot of the material that were getting is going to be not just the book but our discussing in class during our class time here so I'll be expecting you to kind of learn from what were doing here and what I say. So in order to make that easier I hope my goal is to record our lecture and maybe later the discussion so I do have a tape recorder going right now and I will post audio of those recordings so that as you work through the class you're going to be expected to know not just the chapters in the book but what we all talk about. First off, probably I will be talking too much but we will all be talking. So what we come up with will also be material for you to learn. So that leads to a dilemma because if I am successful (there's always going to be technical problems) but if I'm successful in recording the class and putting the recordings online, and that is going to be material you have to use, then you don't have to come to class, right? I mean, technically you could just study online and you wouldn't have to come here, except then there would be only the book, because the no one would be here. So that means that attendance is required at class. Not because I am mean and feel you wouldn't love me if you didn't show up, but the class is part of your work of the class. Being here is part of your work of the class, so there will be an attendance policy. . . . There will be no sign in sheet today, your sign in today is just to go online and fill out your name and email address and such on the online questionnaire linked in the syllabus. Then we will see how it goes. . . . Usually I have two [possible] approaches, but I like to wait and see how it works out. One approach [the official approach now] is to say that everybody is allowed two missed classes, but after that there's virtually no excuses in that the only excuses it would be like a religious holiday or something that you tell me way ahead of time, or something really dire, so we'll see how that works. But if it turns out that huge numbers of people aren't coming--if I don't see you in here basically what that means is you're not doing your job as far as the class goes. So we'll see how that goes. I hope most of you will be here, but we will take attendance and will do that now. . . .

In terms of quizzes, midterms, and final, there will definitely be a final exam I have scheduled on the syllabus. There will be a midterm exam October 9 and we will probably have short quizzes on occasion at the beginning of class. I like to have a lot of little quizzes and things just so you can see how you're doing and I'm getting input and you don't have everything piled on two big exams. There will also going to be a kind of ethnographic assignment that you'll do turning in, of which the first one will be the week of September 4 which is Labor Day. I haven't figured that out exactly, but it will be kind of a personal observation blog thing that you will do sort of being an anthropologist and observing. It will be pass/fail. But if I feel like you haven't done a good enough job or complete enough I will say please add to it or do some more. We will have a teaching assistant so I have to talk to him and will be working out the procedure for that. I hope we will be having a lot of input so I'll know how you're doing and you'll know how you're doing. I think there's a new ruling that for core classes like this . . . you're supposed to get interim grade at around the midterm time so you can see how you're doing. So I have to I just saw an email about that so will have to check on that. OK I have here on the syllabus around November 20 team ethnography and global studies assignment I'm trying to work that out. I want to be a little flexible [on teams] because sometimes it works well to have people work together in teams on things . . . I like to do that but we won't have like formal, team-based learning right from the beginning. I want to check with the teaching assistant and see how that goes. Towards the end [of the semester] I hope we will be finished up with the book around the first week or so in November and then will have a little time to get ready for the final and do some kinds of small assignments. There will not be a big paper or any kind of research paper, but I'll expect you to be doing and will go into this more a certain amount of ethnographic writing where you go out and you just observe stuff having to do with other cultures and write it up. Again, it's not like a research paper, but I will be looking at your writing and sending it back if it needs more. But part of being an anthropologist, the sort of methodology, I hope you learn, is the special kind of writing ethnography -- ethno meaning people graph meaning drawing sort of people graph picture people description -- is a kind of writing which you'll see a lot in this book, which is trying to be descriptive of other cultures, of phenomenon in other cultures and sort of see things in terms of other people you'll see a lot of things [like] we write that are chapters [in the book], some of which are funny, some of which aren't that are like descriptions of cases where anthropologists hugely misunderstood what was going on in field.

So what I want to do now for just about 20 minutes is give you a quick overview of sort of (A) my background how I fit in as a teacher this class--my perspective and then (B) this key concept of culture which we are going to be hammering on in the first three weeks of the class [and] is really central to anthropology but is also really hard to explain or define. In fact it's something that most anthropologists disagree on.

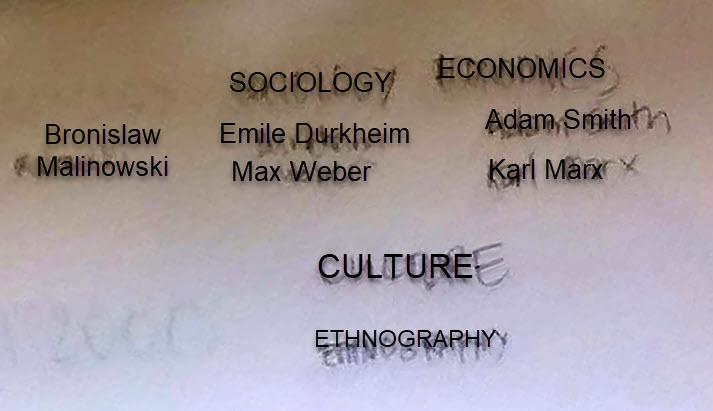

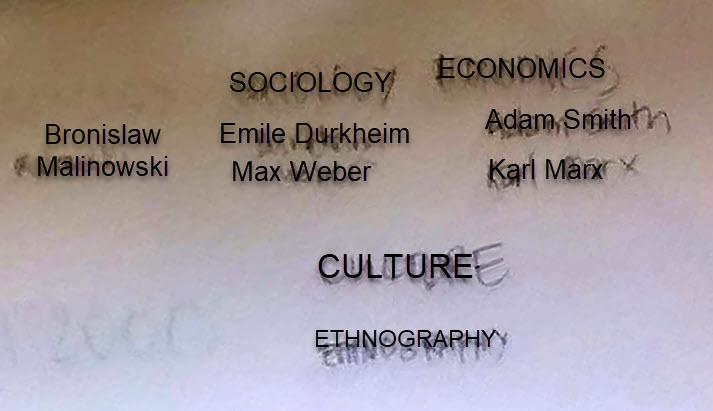

OK, so what is anthropology . . . yes . . the study of mankind. Okay, but isn't sociology the study of mankind? Isn't psychology the study of mankind? There are a lot of fields that study mankind. Any other thoughts? . . . [there are definitions of the different fields but the reality is that they all kind of study everything . . . It's sort of like to me [for] all the social sciences, basically what happened was during the period from the Enlightenment to the emergence of capitalism and Western thinking and all this stuff . . . Before [that] probably you could say that theories about people, how they worked, what went on inside them in their psyches and their souls, and in society and everything were in various forms that certainly were philosophical and had a lot more religion involved [particularly] in the sense that in major societies that had a lot of writing and a lot of people that wrote stuff and spent a huge amount of time talking about it [note Prof G they were talking about major [often] written [usually] verbalized texts] . . . I mean every society in the world had that. But in the West, in Europe, and later the USA . . . the period of the Enlightenment led to the development of the different social sciences. And now, we sort of define them in an organized way, but [then] there were different groups of people who thought of different things so there was an enormous overlap between the different fields. So when I say anthropology around the 1800s there were people starting to . . . say they were anthropologists and there were other people who we think of is sociologists so . . . if you kind of went through from like it 1820s, 1830s, for 100 years you saw these fields kind of developing but in fact there was huge overlap. So for example, Durkheim sort of think of in terms of sociology. A little bit later, Malinowski is an anthropologist and then we have people sort of economic theory, but the reality is that there is huge overlap, I mean. So for talking about the history of anthropology, of anthropological thought in the ideas that develop, we're going to see Durkheim and Weber and Marx in particular is much as we see Malinowski. Now this class is not a class in the history of anthropology (there is a course in anthropological theories that will cover that more). There probably will be a few names that you'll have to learn, just so you don't get me in trouble later on by not knowing them. But the fact of the matter is they were all curious in the last century [the 1800s] about different peoples in the world and you know there's a huge amount of overlap [in their approaches].

The key thing is that in this time, let's just say, starting even the mid-1700s, this big thing happened, that capitalism emerged, all this stuff happened and that was the issue for all these people, like there was this massive change that was happening in Europe and at the same time as this was all happening in Europe, the transformation of the economy from feudalism to mercantilism or whatever, all these different theories that you have, things were really different, so a lot of people like Durkheim and Weber and Marx where all saying "what happened; what was this huge change?" and then at the same time there was this big change in economy [I'm being incredibly simplistic here]. So this was Europe and what we call the Western world.

But then there was the question of what about everybody else? Because at the same time this was happening, European powers were going out and establishing colonies and taking over everything, and missionaries were going out, and there was a lot of interaction with some big civilizations like China, and so on. Europe was conquering the New World and finding big civilizations there too and so on. So, well, we had the Western world, but what about everybody else? So that was the part [the question] that got anthropology started. So anthropology -- anthropologists were very focused on this question of "what changed?" [but in terms of] What about all these other people . . . seems like maybe they didn't change . . . how did that happen. The focus of anthropology was to look at other people and see how they were different. So that's kind of what gave anthropology the start historically. Even though in terms of content, there's a lot of interaction with sociologists, economists (I haven't put psychologists who were more focused on the European situation itself, and what changed). But the kind of underlying stuff was similar [for all these fields]. This is something that on the one hand [in] anthropology, there is a focus on other societies and cultures, but at the same time there is a focus on the difference between [the West and] everybody else. So anthropologists were doing two things (1) looking at other cultures. That's the sort of specialty of anthropology of looking at different cultures but at the same point (2) developing along with these other people theory about how this big change took place. So like, even today, if you take other courses in anthropology you'll see a lot of emphasis on ethnography and studying cultures, different societies, how they work, but you'll also see in areas like critical anthropology where people are looking at this enormous change that occurred with the development of capitalism, which, like changes [note: even distorts] our ability to see everything. So that's a big thing that we will be wrestling with. [question about can you describe effect of capitalism] I can't really [answer the question] as of yet because part of what will be doing is looking at the theory of that. But all of these people and the anthropologists picked up [from] Durkheim, for example, Durkheim sees that in this period of time there was a huge change from societies that were organized more on the basis of emotional ties sort of symbolic stuff to a more kind of what he called organic like the organs of the body working together that capitalism was more sort of machinelike sense of modern society, and [that is a] big difference. Other people talk about differences of scale and things like that will see. And then there's another whole thing that a kind of whole ecological approach which I really favor, which is that during this time there was an enormous change in the relationship between energy and production. You know mechanical energy allows replacement of human labor and all this kind of thing [the theory of it]. We'll get in to that too . . . but there was also an enormous drug that happened [suggestions from class -- caffeine? opium?]. No yeah one thing that people have always had to use solar energy and water to produce food, so food and wind and all these things and they started you know using some mechanical stuff, but suddenly it turned out that -- you know the old situation where solar energy was a source of energy and you could only use it by dealing with plants that were produced -- they found out that under the ground there was a lot of old rotted plants there and carbon you could pull out and bypass the [the old slow process] and produce huge amounts of energy to kickstart [production] -- the argument is that was part of the whole Industrial Revolution and change. It wasn't just change of economic circumstance, but there was also all this [new] energy available to produce stuff. . . . we will get into some of those theories too.

[Eclipse] that's going on, okay so we'll stop around two [pm] so let me just take five more minutes. I wanted to give you little bit of my background and the big things of this beginning chapter [Section One to read by next class] [which] are culture, the idea of culture, and then this method called ethnography. So when you read these first chapters . . . I guess maybe I won't even try to define them [now]. Culture is like almost impossible to define anyway. But what I'd like you to do is between now and [next class] is to get the book and read those chapters.

So okay so as far as my background, I am an anthropologist. I am a very ancient anthropologist. I got my PhD in 1970, believe it or not, and I had already done like eight years of fieldwork before that. It does have some practical consequences like I'm pretty deaf and I have the choice of putting in my hearing aids, which means with my voice, I just blow out my eardrums. But what it means is if you ask a question, if you don't speak up, you'll find me having to bound over to where you sit and listen to you. [question: where did you study?] I got my PhD at Stanford in what was called linguistic anthropology. I did my first fieldwork in West Africa, and then I worked in Mexico, did some work in Guatemala, so I've been kind of around unfortunately didn't really learn Spanish very well in those days, even though I taught at university in Mexico for a couple of years and I studied agriculture in Mexico. Then I went to Southern California and I came to FIU in 1981, and I've been here ever since. And it's hard to, like say, but I really feel like I'm a total anthropologist, but I also ran a survey research Center. I do a lot of work in geographic information systems. I've worked over ... years doing the FIU Cuba Poll with Prof. Guillermo Grenier, we've done that.

So even though you'll see I think I'm a total anthropologist I'm tremendously interdisciplinary at the same time. I just five days ago I put in our proposal with Dr Weirui Wang in communications and Dr Mary Jo Trepka in epidemiology to study Zika -- the whole Zika crisis in South Florida which has tremendous ramifications of culture and countries and all kinds of things. So I'm very interdisciplinary but I think you'll see that in that I am totally, in terms of culture and ethnography, an anthropologist. [Which is useful] if you become interested in anthropology. It's one of those weird fields where there's not a whole lot of high-paying jobs for a quote anthropologist and yet I do all kinds of work in all different areas where I feel like I'm working as an anthropologist interacting with other people. I'm like, I'm also on a working group at the National Hurricane Center where we oversee testing messages that are coming out like -- if you go and look at the next hurricane [forecast] you'll see a new [graphical] product. It tells you the estimated time when hurricane force winds are going to arrive. That's a new product this year and they've been testing it out, and the problem is, there's a big cultural problem because like, when is that exactly? Well it is over a range of time and what do people really want to get? A warning to get out with no regrets, which means much earlier than when it's most likely to arrive. You know that's kind of a cultural question because different people, different psychological views. Some people/culture say no. I just want the facts of when it's supposed to arrive. Let me figure out the earliest possible risk and other people say, no, how am I going to figure that out? -- I want to know the time when, if I get out by then, I know I'm going to be safe. So it's cultural.

okay

so that's it. Again, the problem is were all going to

be talking and there is going to be material in the

class that we generate from our discussion -- so part of

your work. I hope the recording works and I can put

the audio up for you to listen to and we'll

build that into the materials.

Okay see you next

week.